Hiding the Moon by Chris Castle

Willis Broad woke early on the last day and stretched at the end of his bed. He felt his bones creak just about as bad as his floorboards but stopped himself from sighing. As he made his way to the shower, he glanced out of the window and saw it was going to be a clear day. After he dressed, with a single glance to the mirror to check his belt buckle, Will brewed coffee on the hob and waited.

Willis Broad woke early on the last day and stretched at the end of his bed. He felt his bones creak just about as bad as his floorboards but stopped himself from sighing. As he made his way to the shower, he glanced out of the window and saw it was going to be a clear day. After he dressed, with a single glance to the mirror to check his belt buckle, Will brewed coffee on the hob and waited.

His daughter arrived a few minutes after he’d settled on the porch. It would have been okay if she had been late but he was glad she'd showed up on time, nevertheless. The car gathered up on the kerb like a bright red tornado and she stepped out with a grace that immediately made Will think of her mother. His arms were already open and she dashed into him, almost the same way she did as a kid. Like then, he fought to make himself let go; it was only the knowledge that she would be smiling when they slipped apart that made him.

After coffee, the two of them walked to the main strip, exchanging ideas and gossip at a furious pace. Willis had learned to sign as soon as the doctor told him his daughter would be deaf and by the time she was born he was almost fluent. By the time she was six, it was as natural as breathing for both of them. He loved the way his palms hummed as they spoke and it always reminded him of music, the way his hands used to ache after playing guitar.

He opened the restaurant up at nine sharp, wincing as he always did as the metal shutters clattered into life. The graffiti looked tired against the steel and the messages had been there so long he knew them all off by heart; one more little detail he’d miss, as he secured the rafters in place. Will threw the keys back for his daughter to open up.

She hesitated for a moment and then stepped forward, jamming it in the lock and opening it first time. He put his arm around her as they stepped inside the place for the last time.

He changed into his outfit and handed her a white shirt, a hat, gloves. Without another word she stepped out front and filled each of the salt and pepper shakers and wiped down the sauce bottles. After eight years the only regret Willis had was that his daughter had only been able to come and work with him for two summers. Would it have felt the same if it had been every summer? He didn’t know and was not so sure he wanted to find out the answer. The coffee boiled and he filled both cups as he opened the fridge to see what was left.

A few regular customers drifted in for breakfast and made small talk. They joked good- naturedly with him, wondering out loud where they were going to get coffee so good and eggs so cheap. Will told them of a few places and winked as he told them they were ‘ almost as good.’ When it came for them to leave, each one of the guys left a good size tip and stepped over to shake his hand. It was the handshakes that mattered; those small, simple gestures that make up a day, a life. He thanked them all and saw them out.

Danny was the first shop keeper to come by, at around eleven. As big as he was, he always opened the door soundlessly and always reached a table without so much as a sound. Will had kidded how he would have made a good cat-burglar and the big man’s answer, poker-faced every time, was always the same; ‘ how do you know that I’ m not?’

“Beautiful day to shut up shop, Will,” he said, accepting his coffee. “You closing at five, same as the rest of us?&rdquo

“Sure. I’ m still cooking up what’s left. You all come down any time after you’re done, okay?” He slipped the eggs in-front of him and waved Danny off as he reached back for his wallet.

“You sure? Then much obliged.” He looked past Will to the street. “Knocking down people’s livelihoods for condos. I don’t know what’s right but I know what’s wrong.” He shook his head and then looked back over to Will, smiling. It took ten years off the man, if it took a day.

“Everyone will be here, Will. You try stopping them. I see Amy out the back?” He looked past them to the counter. “She come to see things through?”

“She has. I think she was worried I was going to torch the place or something.” He shrugged and sipped his coffee, looking around. The walls had odd squares of uneven colour where the photos had been taken down. It had made him impossibly sad at first but now he thought they looked kind of beautiful.

“Hell, if the estate agents weren’t paying so much my hands would smell of gasoline. Smart girl, your daughter. How’s her ma doing?” he finished his coffee and turned the mug upside down on the saucer like he always did.

“She’s doing fine by all accounts,” he said and took the cup. Short phone calls and long reams of bills. He could feel the other man looking him over but knew he wouldn’t ask anymore. “Hell, you got a beautiful daughter, Will. Only thing I ever got was alimony and gout. Five it is,” he said, standing suddenly. “I’ ll spread the word to the others.”

“You do that,” Willis said, opening the door and seeing him out down the street.

The road was empty now; most of the shops were boarded up now, a few with windows smashed in, not that it mattered. Soon it would all be gone and houses would be sitting pretty in their place. He wondered if any of them would have grown-up locally and then shook his head, knowing it didn’t matter a damn, either way. Everything kept moving and everything changed, he thought. The only thing that stayed the same was the past.

By lunchtime, the two of them had set up a card game, with matchsticks for stakes. Amy had turned into a mean poker player and he was glad college life was teaching her a trade at least, though he hoped that wasn’t the only thing. The photos she had sent of herself, looking almost unreal in her beauty, the ballet shoes scuffed and the costume worn with honour, told him he had little to worry about on that score.

When she had set off so far away his heart had broke, as he had expected it to; but then he found something in it, the distance, something good. For the first time since he’ d starting courting her mother, Will wrote letters; long, careful letters that told her the facts and offered enough of the truth between the lines if she was prepared to look for it. He had alluded to how much he had loved her mother and the hurt he’ d felt when that love died but without any cruelty or spite. In every one he had mentioned how worried he felt but also how proud he was for her in claiming her freedom. Sometimes, as he wrote, he became aware of how little he knew about his daughter but also how much there was still to learn in the future.

Will sometimes wondered about his own life; how it had come to pass that he issued all his best intentions without talking; that everything was wrapped in paper and skin and there was never a true word spoken clearly, face to face. He wondered some nights what words he had used too often or not enough. Sometimes, in his dreams, he saw specific words; the ones that could have saved him and the ones that had sunk him for good. On those nights he woke up sweating, reaching for the notebook he had taken to keeping by his bed, but by then they were lost.

At midday he stood up and suggested a light lunch and was surprised when Amy pushed him back down. He fought half-heartedly and then threw up his hands in defeat. She walked away and he counted to ten before he followed her out back, where she broke eggs into the pan; always eggs, always just right. As if she had read his mind, she looked up and smiled and then ushered him out with a wave of her hand. By the time they arrived in front of him, he was surprised at how peckish he felt. After they had put the cards and the toothpicks to one side they sat and both carefully dusted the plate with black pepper and nothing more. Will walked over to the door and locked it, even thought the street outside was deserted. It just seemed the right thing to do; as he walked back and saw his daughter beaming at him, he knew that it was.

A grand total of six customers wandered in over the course of the afternoon, each of them only ordering coffee. Even so, Willis noticed his daughter’s surprise when he flipped the sign over to ’ closed’ at three thirty. He waved away her protests and led her over to the counter. As he lifted the boxes onto the surface he was careful to keep his eye on her, to see the surprise in her face as he laid out the food in front of her. Her shock turned to a smile and as it went on, into pure joy. Of course everyone had assumed he would be cooking up the scraps and leftovers and originally that was what he had planned to do. It wasn’t until he had sat outside the restaurant and looked down the empty street a few nights before that he realised how much he would miss the place. How a good part of his life, no matter how difficult or at what cost, had been tied into this small building in this desolate street. A year from now, he thought as he lit one of his occasional cigars, there will be no trace of this place at all. Suddenly, the scraps didn’t seem like a suitable farewell at all. Don’t e a hand, when you can give a two finger salute, his old man had always said.

The menu had come to him that very night.

It was the type of dishes he had dreamed of preparing when he had learned how to cook. One or two of them he had actually made, on his honeymoon night, an anniversary, but others remained just recipes on a page. Now, as he outlined his plans with his daughter, he wondered if that was part of it too; wanting to break the cycle of words and paper and instead make something real, real enough to touch and savour. He went on, his hands moving so fast his nails almost took skin from his palm and watched as his daughter nodded, enthusiastically agreeing, suggesting, arguing. By the time they’ d actually taken the knives from the drawer, he felt a flush of excitement run through his cheeks and looked up to see it mirrored in Amy’s face.

It took hours; it took no time at all. Will couldn’t remember being so happy for a long, long time. He moved the blade like a pencil, then like a scalpel and relished the sensation of his fingers aching with the effort.

One course followed another, the ovens whirring and humming into life, one dish browning as the next began to glaze. The room itself was a maze of aromas and like nothing he’ d ever known. At one point he closed his eyes to take it all in and opened them to see his daughter watching him. He could have felt foolish but her smile made him feel energised and … proud. For a while his heart soared and the next moment seemed to unfold and unlock and become an opportunity; to seize and mould and plunder.

The first rap on the door was on the dot of five thirty. Will wiped down his hand and was pleased to see it was not just one person but almost everyone, save Selena. He waved and jogged out, unlocking the door and welcoming them in. Each of them opened their mouths and then paused as if they’ d forgotten how to speak.

Mr. Tremlett, the barber, searched the room, as if the scents and aromas were an actual person to find and shake by the hand. Mrs. Peake, the seamstress who owned the haberdashery shop simply smiled, as if she was slowly remembering something, something that was good and true. Mrs Boyle and Mr Digress turned and faced each other, as if the answer was written on their foreheads. Finally, Danny broke the silence, breaking out into a wide grin and slapping Will on the shoulder.

“That’s no bacon sandwich I’ m smelling, is it Will?” He said, the others dissolving into laughter and then bombarding him with questions.

He introduced Amy as they sat around the long oval table that Will had bought with big groups in mind and had never once filled. The initial awkwardness subsided almost immediately when it turned out Mr. Tremlett signed almost as smoothly as either of them. The old man positioned himself towards the middle of the group, acting as a bridge for any half-caught words or hurried questions. As Will spoke of his daughter, he pointed to the ballet photos which he had taped, over her protests, on the odd, uneven squares of colour where the framed pictures had once sat. The flood of questions and compliments then directed to his daughter afterwards were nearly as great as the enquiries made about the dishes when they’ d first arrived.

Selena arrived a little after six and he met her at the door. He walked her in and everyone greeted

her at the same time, almost to the point where it sounded as if they were chanting her name. He pulled out her chair and quietly realised that all of them knew he was a little in love with her. Everyone else at the table smiled as if they held a secret or looked away, almost embarrassed on his behalf. The bigger bombshell was Amy, he thought, who immediately looked over to her as if she was already someone she knew and had come to trust. He excused himself in a kind of daze, the truth of what was before him making his head gently spin, as if he’ d just stepped o f a fairground ride that was just the right side of exhilarating.

Amy and Will brought the food out, under offers and protests of help and the meal began. As they ate the conversation drifted to the food, almost as if none of them could help themselves; Will knew he couldn’t. As much as they appreciated the food, it seemed to bring out something else in them, too. As they went round the table, one and then the other seemed to recall a memory, a moment that was good and almost perfect. The food continued to be eaten, neither fast nor slow and their eyes grew heavy in satisfaction, their words more honest.

By the time it was over, the dishes were piled high and the candles burned low. As they said their goodbyes, each of them made heartfelt promises and pledges that were impossible to keep. At the door, Danny bear-hugged both Will and Amy at the same time and slipped a cigar in his short pocket as his daughter rolled her eyes. He knew Selena wanted to stay and help but at the same time knew the last part of the day was meant for him and Amy alone. They said goodbye on the step, the door ajar just enough to shield their kiss from Amy.

It took a while to wash the dishes but both of them were happy enough to be on their feet and burning off a few of the calories. The scent of the dishes gradually faded; in the morning he would clean it one last time and the whole place would be drenched in bleach. As Amy brewed their last cups of coffee, he walked around prising the photos from the wall and slipping them back in the folder. She brought it out and he smiled as he took the mug from her hand. One day there will be a ring on that finger, he thought suddenly and wondered who and when that would all be. He looked around and felt how empty the place was without everyone sitting around and knew Amy felt the same.

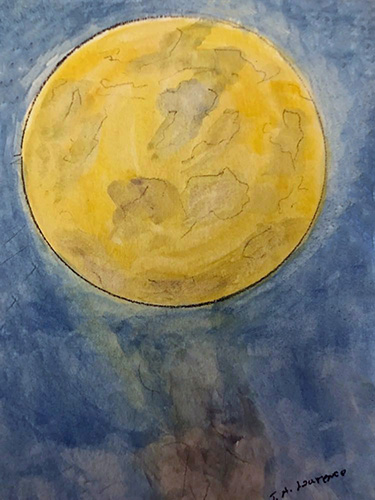

The night was cool and refreshing after the long day as they sat on the step. Will drew the cigar out of his pocket and watched as Amy raised an eyebrow. He lit it and after one or two drags, she gently pulled it from his fingers and took a hit. He wondered how shocked his expression must have been to make her laugh so loudly. The smoke drifted away from them, up to the sky and the stars. Will looked up and found the moon, as his daughter’s hand slipped inside his and filled him with warmth. He felt her rest her head against his shoulder and he smiled, blowing a stream of smoke high into the night and covering the moon for a brief, perfect moment.

###