Passages: Ford Madox Ford and Parade’s End by Stephen Zelinck

[Ford Madox Ford, 1873-1939 was a major force in modernism, advancing techniques now commonplace in prose fiction. He never earned the celebrity of Conrad or Hemingway, but some consider him the greatest 20th cen- tury novelist.] These days, I probably know a book from its mini-series or audible. I may not have read what the author put on paper, deliberated over, and decided on. A slow reader, I consider the author’s intention and his delight in writing those particular words – voiced with pauses and asides -- and even what the writer imagined my response might be. Ford’s work pays dividends for slow readers like me.

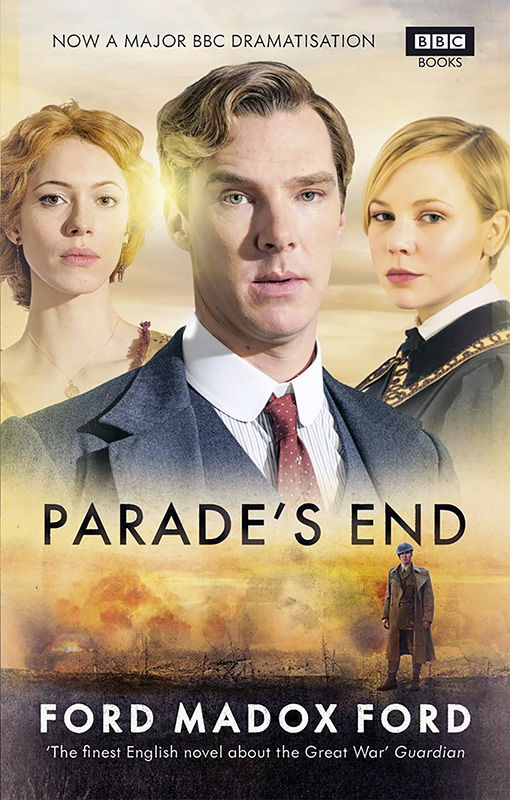

When we think great British modernists, we think Joyce and Woolf, Conrad and Lawrence, or late Henry James. If we know Ford, it is The Good Soldier (1915), with a broken narrative, multi-level interior reflection, and unreli- able narrator, in one taut volume. Parade’s End is grand in conception, Tolstoian in depicting love and war, and often recalling Dickensnd Thackeray in social satire.

Parades End targets the corruption of England’s national character and the crisis of psychic stability. Ford reaches back to the 17th century and forward to the Great War’s end, when no British gentleman could stay sane and intact. The delight in the trilogy, with its sweeping historical views, rests with its gemlike passages, Ford’s wit and his capture of restless minds pondering.

Early in Some Do Not, appears this following wonderful, disjointed rant, issuing from the otherwise sober Christopher Tietjens. In this passage, he’s off on a tear about his scandalous wife and her circle of wealthy, post-Victo- rian ladies:

What’s the sense of all these attempts to justify fornication? England’s mad about it. Well, you’ve got your John Stuart Mills and your George Eliots for the high-class thing. Leave the furniture out! Or leave me out at least. I tell you it revolts me to think of that obese, oily man who never took a bath, in a grease-spotted dressing-gown and the underclothes he’s slept in, standing beside a five-shilling model with crimped hair, or some Mrs W. Three Stars, gazing into a mirror that reflects their fetid selves and gilt sunfish and drop chandeliers and plates sickening with cold bacon fat and gurgling about passion.

Tietjens attributes the behavior of his wife and of her morally disheveled voluptuaries to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). The PRB loosed its dark liberations among better behaved Victorians, including J.S. Mill and George Eliot. The Liberals’ higher truth left Tietjens’ generation morally adrift and at odds with essential British institutions. Tietjens’ disgust is palpable and Ford’s prose wicked -- and, as nephew of Rossetti, “that obese, oily man,” Ford should know.

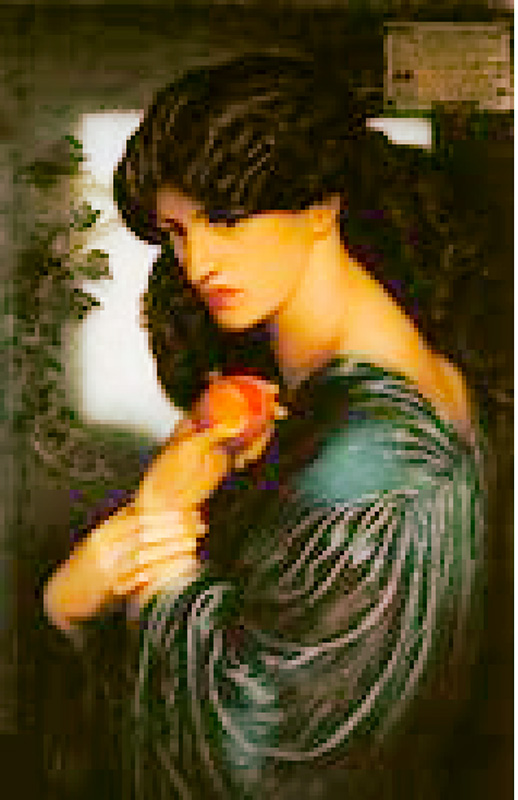

Ford includes Rossetti’s influence as part of the modern rot. Vincent Macmaster, Tietjens’ friend and foil, advances his career in administrative service by publishing a dreary tome on Rossetti that wins him entry into the world of the literary salon. His wife recalls Rossetti’s dark Persephone. The Macmasters barged into polished society from lower middle-class Scottish origins by imitating, in fractured form, what Tietjens as a member of the ruling class inherits as legacy:

Macmaster had achieved his desire: even to the shortbread cakes and the peculiarly scented tea that came every Friday morning from Princes Street. And, if Mrs Macmaster hadn’t the pawky, relishing humour of the great Scots ladies of past days, she had in exchange her deep aspect of comprehension and tenderness. An astonishingly beautiful and impressive woman: dark hair; dark, straight eyebrows; a straight nose; dark blue eyes in the shadows of her hair and bowed, pomegranate lips in a chin curved like the bow of a Greek boat

Both Tietjens and Macmaster work in the Bureau of Statistics, where Tietjens excels at the mathematics of it. Statesmen use the Bureau to support party politics. In war time, statistics justify material support, movements of troops, and fortunes to be made. Tietjens, adhering to calculations and reliable analysis, is no use at this. Macmaster, in contrast, is ambitious and agreeable. He provides politicians the statistical interpretations they need. For this, Macmaster attains a title, and Tietjens, a posting to the trenches in France. A staunch 18th century fellow, Ford’s hero entertains a Swiftian view of modernity and wields sparkling prose:

And Tietjens … fell to wondering why it was that humanity that was next to always agreeable in its units was, as a mass, a phenomenon so hideous. You look at a dozen men, each of them not by any means detestable and not uninteresting: for each of them would have technical details of their affairs to impart: you formed them into a Government or a club, and at once, with oppressions, inaccuracies, gossip, backbiting, lying, corruption and vileness, you had the combination of wolf, tiger, weasel, and louse-covered ape that was human society.

Satire, some say, is conservative, measuring the madness against traditional standards, without apologies. Challenged as a Socialist for his unconventional views, Tietjens explains:

But I’ve no politics that did not disappear in the eighteenth century ... -if it’s Sylvia that called me a Socialist, it’s not astonishing. I’m a Tory of such an extinct type that she might take me for anything. The last megatherium.

In a bit of self-deprecating fun, Tietjens proceeds to portray the sort of Tory he is:

a great English Landowner, benevolently awful, a colossal duke who never left his study and was thus invisible, but knowing all about the estate down to the last hind at the home farm and the last oak: Christ, an almost too benevolent Land-Steward, son of the Owner, knowing all about the estate down to the last child at the porter’s lodge, apt to be got round by the more detrimental tenants: the Third Person of the Trinity, the spirit of the estate, the Game as it were, as distinct from the players of the game: the atmosphere of the estate, that of the interior of Winchester Cathedral just after a Handel anthem has been finished, a perpetual Sunday, with, probably, a little cricket for the young men.

Perhaps we read fiction to enter imaginary realms, or to experience vicariously what we wouldn’t dare or couldn’t afford, or to have our prejudices petted, but sometimes the joy is in turns of phrase and delightful play of references. Imagining “Christ" as an estate-keeper, is full of fun, including the self-deprecating notions of an Englishman’s fantasy Sunday, a heavenly end to a complaisant week. Ford is master of this spiritual circle of fifths, the mockery of Handel gone sour, and an interior wandering, listening in to consciousness and the loose vagaries of fractured intelligence. Tietjens’ bitterness comes not from below but from a ruling class viewing itself in collapse.

[Edith Ethel Macmaster fashions herself after Rossetti’s Persephone, sexually menacing and cruel.

Critics praise Parade’s End as a great WWI novel, high praise given the number and quality of them. Shots are fired and trenches explode, but Ford concentrates on tedium, greed, and depravity. Ford served in the trenches, surviving explosions that rattled his senses. But his principal interest lies behind the lines: modern administration and mad crush of things and of people:

Base depots for infantry, cavalry, sappers, gunners, airmen, anti-airmen, telephone-men, vets, chiropodists, Royal Army Service Corps men, Pigeon Service men, Sanitary Service men, Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps women, VAD women “ what in the world did VAD stand for? “ canteens, rest-tent attendants, barrack damage superintendents, parsons, priests, rabbis, Mormon bishops, Brahmins, Lamas, Imams, Fanti men, no doubt, for African troops. And all ready dependent on the acting orderly-room lance-corporals for their temporal and spiritual salvation . . . For, if by a slip of the pen a lance-corporal sent a Papist priest to an Ulster regiment, the Ulster men would lynch him, and all go to hell. Or, if by a slip of the tongue at the telephone, or a slip of the typewriter, he sent a division to Westoutre instead of to Dranoutre at one in the morning, the six or seven thousand poor devils in front of Dranoutre might all be massacred and nothing but His Majesty’s Navy could save us.

Ford anticipates Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, its absurdity and horror. More men are needed to feed the slaughter at the front while workmen to repair the rail tracks to bring them there are not available, and so war planners "French and English" war among themselves on whom to blame. Back in London, politicians argue whether the English should submit to a unified command, under French administration. Some English generals, close to the action and suffering London’s indecision, support the One Command policy. In retaliation the Home Office withholds replacement troops, all but guaranteeing the defeat of their armies and thousands of casualties. “General Puffles, as the cartooned commander is called, frustrates the Home Office by holding the line, despite all London can do to increase losses. Meanwhile, trench warfare horror proceeds:

And, suspended in them, as there would have to be, three bundles of rags and what appeared to be a very large, squashed crow. How the devil had that fellow managed to get smashed into that shape? It was improbable. There was also suspended, too, a tall melodramatic object, the head cast back to the sky. One arm raised in the attitude of, say, a Walter Scot Highland officer waving his men on.

Ford will not miss the opportunity to set the ideals of literary imaginings against the ghastly ballet of inglorious slaughter.

Tietjens attributes this madness to the growing anonymity of troops to one another. This mayhem would not occur if England’s armies were arranged by local regiments, preserving the bonds of men to each other and the officers to their men. Instead, the military transforms men into strangers, often speaking dialects unintelligible to one another:

It isn’t the officers and it isn’t the men. It’s the foul system. You get men who think they’ve deserved well of their country “ and they damn well have! “ and you crop their heads . . . ’ That’s the MOs,’ the dark man said. ñThey don’t want lice.’ ñIf they prefer mutinies . . . ’ Tietjens said. A man wants to walk with his girl and have a properly oiled quiff. They don’t like being regarded as convicts. That’s how they are regarded.’

Tietjens is a stranger to his world. As an officer, he cares for his men, and not only for their utility. His Yorkshire family estate is agricultural and, in its best tradition, depends on caring for and good relations with tenants. Tietjens won’t torment workers for profit. His view is traditional, organic, and harmonious. The war makes this worse, prizing the estate’s coal deposits and despising orderly life and the cycles of nature. The point, as Tietjens’ Sergeant-Major insists, is to preserve from destruction that “bleedi’ ill, a man could stand up.

Reaching back several centuries, Tietjens’ ancestors had not distinguished themselves as soldiers. They have exceled instead at maintaining their estates. Christopher, a second son, had little expectation of commanding his estate. He turned his attention, instead, to irrigation and crop rotation. He knows soil, trees and flowers, birds and small animals “ Gilbert White’s lore and affection in Natural History and Antiquities of Selborne (1791), the real and enduring England. This technical knowledge serves Tietjens well in the trenches. He excels also at record-keeping and quick estimates of supply. However, his strength as an officer comes from understanding his men’s needs as they face war’s horrors and the heartless dealings of those who manage the war from a safe distance.

Do you think it makes any difference to them what officers they have?’ Tietjens asked. Wouldn’t it be all the same if they had just anyone?’ The Sergeant said: No, sir. They bin frightened these last few days. Now they’re better.’ This was just exactly what Tietjens did not want to hear. He hardly knew why. Or he did . . . He said: I should have thought these men knew their job so well “ for this sort of thing “ that they hardly needed orders. It cannot make much difference whether they receive orders or not.’ The Sergeant said: It does make a difference, sir,’ in a tone as near that of cold obstinacy as he dare attain to ...

Tietjens would prefer not to carry such responsibilities. Sergeant-majors, career men from humble beginnings, value good leadership. Tietjens rails at those who run the war for profit and promotion and at the upper classes grumbling at inconveniences. Tietjens’ wife finds the gunnery units defending her inconsiderate, disturbing her peace. The upper crust hold soldiers in contempt:

Amongst Sylvia’s friends a wangle known as shell-shock was cynically laughed at and quite approved of. Quite decent and, as far as she knew, quite brave menfolk of her women would openly boast that, when they had had enough of it over there, they would wangle a little leave or get a little leave extended by simulating this purely nominal disease, and in the general carnival of lying, lechery, drink, and howling that this affair was, to pretend to a little shell-shock had seemed to her to be almost virtuous.

At Armistice (11/11/1917 at 11:00 AM), the fashionable folk, having done nicely during the war years, contemplate with alarm the return of their fighting men:

There were such a lot of these bothering War heroes that if you let them all into your Salon it would cease to be a Salon, particularly if you were under an obligation to them! . . . That was already a pressing national problem: it was going to become an overwhelming one now ... The impoverished War Heroes would all be coming back. Innumerable. You would have to tell your parlourmaid that you weren’t at home to . . . about seven million!

Ford’s satire, Dickensian in this, adopts the interior dialogues of entire social classes, mimicking their complaisance and comfort.

War was a slaughterhouse for many; for others, a great boon. Tietjens’ brother Mark, a government administrator, has this to say about prospects in war:

You saw we proved the estate at a million and a quarter as far as ascertained. But it might be twice that. Or five times! . . . With steel prices what they have been for the last three years it’s impossible to say what the Middlesbrough district property won’t produce . . . The death duties even can’t catch it up. And there are all the ways of getting round them.’

Worse are the administrators in snug government offices, managing the war from afar and with no responsibilities to those in the field. Tietjens’ comments are fierce, hid just below a polite layer of irony:

All these men given into the hands of the most cynically carefree intriguers in long corridors who made plots that harrowed the hearts of the world. All these men toys: all these agonies mere occasions for picturesque phrases to be put into politicians’ speeches without heart or even intelligence. Hundreds of thousands of men tossed here and there in that sordid and gigantic mud-brownness of midwinter . . . By God, exactly as if they were nuts wilfully picked up and thrown over the shoulder by magpies …

Passages like this remind us that Ford was a poet, admired by T. S. Eliot, and Pound, and dozens in the decade after his death. His rhetoric shines with feeling and intelligence. Tietjens experiences the fog and folly of war from the trenches. Policies emerge from the polished corridors in London and Paris, but the madness happens in the mud.

[Trench warfare and its misery dominates Parade’s End. Ford served at the front and sustained injuries that sent him home “shell-shocked.]

The ruling class has abandoned its leadership and codes of honor, opening the doors to administrators and managers, bankers and press barons, and sharp-dealing politicians. Tietjens’ progress to the trenches follows a clash between the army’s needs and the power of a newly-minted Lord of foreign origin.

Assigned to transportation services, Tietjens cares for the stabling, exercise, and health of the regimental horses. And then Lt. Hotchkiss, right out of Dickens, comes to assume those duties. He is a professor of equine physiology, without experience of the army, of warfare, and remarkably, of horses outside of books.

Hotchkiss has been tasked to produce superior racing steeds. Hotchkiss’ patron, a powerful newspaper magnate, uses the military to advance a scheme. Denying horses a heated stall in winter, proper food, and personal care will toughen them and enhance Lord Beichan’s stable. Lord Beichan, a foreigner, cares nothing for England’s war effort. He pursues instead war’s opportunities:

The Earl of Beichan, a Levantine financier and racehorse owner, was interesting himself in army horses, after a short visit to the lines of communication. He also owned several newspapers. So they had been waking up the army transport-animals’ department to please him … a Veterinary-Lieutenant Hotchkiss … had come to them … at the request of Lord Beichan, who was personally interested in Lieutenant Hotchkiss’s theories … Tietjens, his breath rushing through his nostrils, swore he would not go up the line at the bidding of a hog like Beichan, whose real name was Stavropolides, formerly Nathan.

Tietjens, ripe with Tory intolerance, despises the growing influence of foreigners. It is not just the energetic Scots, the Welsh, and the Canadians, but the seepage into political power of sharp dealers from the Levant. Lost is the culture and character of the English in their deepest business. However, Tietjens despises more the ruling classes who have relinquished their ascendency. The war is run by office warriors -- bankers and policy officials -- safe in their corridors of power:

…

Port Scatho had never witnessed a family parting at all. Those that were not inevitable he would avoid like the plague, and his own nephew and all his wife’s nephews were in the bank. That was quite proper, for if the ennobled family of Brownlie were not of the Ruling Class “ who had to go!“ they were of the Administrative Class, who were privileged to stay.

General Campion, Tietjens’ commander, cannot protect him from press barons and bankers. Tietjens, standing firm, must perish for doing the right things.

General Campion steps directly out of Dickens and Thackeray, a blustering tyrant adept at side-stepping responsibility, and aiming always at the next step upward -- for him, a posting to India as Viceroy. Campion is stock English officer. His caricature anticipates Evelyn Waugh and Monty Python:

When Sylvia mocks Tietjens’ goal to model himself upon our Lord . . . ’ The general leant back in the sofa. He said almost indulgently: Who’s that . . . our Lord?’ Sylvia said: Upon our Lord Jesus Christ . . . ’ He sprang to his feet as if she had stabbed him with a hatpin. Our . . . ’ he exclaimed. Good God! . . . I always knew he had a screw loose . . . But . . . ’ He said briskly: Give all his goods to the poor! . . . But He wasn’t a . . . Not a Socialist! What was it He said: Render unto Caesar . . . It wouldn’t be necessary to drum Him out of the army . . . ’ He said: Good Lord! . . . Good Lord!

[Trevor Sewell portrayed Reverend Duchemin, in the HBO miniseries. Even before Duchemin launches into his guests’ habits of masturbation and hauls up his treasured paintings “A fair blaze of bosoms and nipples and lips and pomegranates, Ford lampoons the grandeur of Episcopal]

This same satiric savagery portrays the Rev Duchemin, a sexual deviant and madman, but a figure of ruling class refinement, right out of central casting:

It was extraordinary that anyone so ecstatically handsome as Mrs Duchemin’s husband should not have earned high preferment in a Church always hungry for male beauty. Mr Duchemin was extremely tall, with a slight stoop of the proper clerical type. His face was of alabaster; his grey hair, parted in the middle, fell brilliantly on his high brows; his glance was quick, penetrating, austere; his nose very hooked and chiselled. He was the exact man to adorn a lofty and gorgeous fane, as Mrs Duchemin was the exact woman to consecrate an episcopal drawing-room. With his great wealth, scholarship and tradition . . .

[England, long in decline, war has speeded the process. Empires are founded by pirates and thugs, who only later become high-minded gentlefolk. So it was with Roman landowners pressing outward in conquest. Plato, Polybius, Machiavelli, and Gibbon note empire’s brutal beginning, graceful civilizing, and ugly demise. The journey trends downward into corruption, absurdity, and madness.]

Parade’s End has its title from this exchange between Tietjens and General Campion. Campion is apoplectic at his subordinate’s insistence on forms of decency towards the troops. Tietjens upholds a code of responsibility borne by those adhering to ruling class codes:

Tietjens said: Still, sir . . . there are . . . there used to be . . . in families of . . . position . . . a certain . . . ’ He stopped. The general said: Well . . . ’ Tietjens said: On the part of the man . . . a certain . . . Call it . . . parade!’ The general said: Then there had better be no more parades.

By “parade he means decent behavior, to be adhered to as closely as close-order drill. Ford’s trilogy pursues this notion of decency in love as in war and its politics. Tietjens maintains “parade in inspiring the men under his command and tending to their injuries and fears in the slog of trench warfare. But romance and desire, and the form of marriage, have also been badly damaged.

The women in Parade’s End follow Ford’s scheme of decline and renewal. Sylvia Tietjens, Christopher’s wife, draws upon 18th century elegance and corruption:

Thoroughbred! In a sheath gown of gold tissue, all illuminated, and her mass of hair, like gold tissue too, coiled round and round in plaits over her ears. The features very clean-cut and thinnish; the teeth white and small; the breasts small; the arms thin, long and at attention at her sides . . .

She is born to ease and concentrates on twisted pleasures, chiefly in frustrating men. She is physically alluring but treacherous. She captures Christopher with her sexual allure, has sex with him -- a stranger in a railway car “ claims her pregnancy as the result, and working upon his sense of decency forces marriage. The child may not be Christopher’s, but his code of honor will not permit him to abandon her. Her joy in this is perverse:

I’ve always got this to look forward to: I’ll settle down by that man’s side. I’ll be as virtuous as any woman. I’ve made up my mind to it and I’ll be it. And I’ll be bored stiff for the rest of my life. Except for one thing. I can torment that man. And I’ll do it.

Sylvia is pursued by hapless men, drawn to her languor and exquisite polish:

Men, at any rate never fulfilled expectations. They might, upon acquaintance, turn out more entertaining than they appeared; but almost always taking up with a man was like reading a book you had read when you had forgotten that you had read it. You had not been for ten minutes in any sort of intimacy with any man before you said: But I’ve read all this before . . . ’ You knew the opening, you were already bored by the middle, and, especially, you knew the end . . .

Christopher is the only man intelligent enough to hold her interest but, despite her efforts, remains out of reach. He married her for the sake of the child and keeps up appearances, and an amused resentment, not knowing what else to do.

Edith Ethel Duchemin, wife of a sex-mad clergyman, and after her husband’s suicide married to Tietjens’ friend Macmaster, is a woman on the rise, employing the style and imagery of the Pre-Raphaelites and their obscene luster. She is fashionable and alluring, but ludicrous in her social aggression.

Edith Ethel is just one variation of the licentiousness and corruption let loose by social decline and sketched by Ford’s sharp pen:

Certain of [Sylvia’s] more brilliant girl friends certainly made very sudden marriages; but the averages of those were not markedly higher than in the case of the daughters of doctors, solicitors, the clergy, the lord mayors and common council-men. They were the product usually of the more informal type of dance, of inexperience and champagne “ of champagne of unaccustomed strength or of champagne taken in unusual circumstances “ fasting as often as not. They were, these hasty marriages, hardly ever the result of either passion or temperamental lewdness. Valentine Wannop, Tietjens’ love interest, notes the fashionable promiscuity in those of her generation, but also the lack of passion:

Like most of her young friends, influenced by the advanced teachers and tendential novelists of the day, she would have stated herself to advocate an “ of course, enlightened! “ promiscuity … Actually she had thought very little about the matter. Nevertheless, even before that date, had her deeper feelings been questioned, she would have reacted with the idea that sexual incontinence was extremely ugly and chastity to be prized in the egg and spoon race that life was.

What a delicious paragraph! Though classically educated, Valentine is not acute. She accepts the sexual notions of her day, being advanced and all, yet she knows it is bad advice in “the egg and spoon race of courtship; that is, Atalanta’s ruse in winning her less fleet-footed lover. Ford writes for slow readers but fast thinkers.

Ms Wannop is the daughter of a well-regarded classicist father and a talented novelist mother. Her family is rich in learning but poor in funds and social prominence. Their daughter works for a living, first as a downstairs scullery maid and later as a physical education instructor in a middle-class girls’ school. She lacks Sylvia’s elegance and Edith Ethel’s dark allure. Valentine is something new, after the empire’s fall. Like Tietjens, she is well schooled in Latin and in a naturalist’s knowledge of the English countryside. She is demure, and as with Tietjens, being old-style English, baffled by a hidden current of passion. She asks for nothing from society other than to be left alone to become her best self.

Her initial love scene occurs in a dense fog, lost on the road, with Tietjens, innocently by her side, as they exchange bits of Latin and tags from Romeo and Juliet; she, wary of this strange man, and he, foggy as the pre-dawn country road:

Her otter-skin cap had beads of dew; beads of dew were on her hair beneath: she scrambled up, a little awkwardly: her eyes sparkled with fun: panting a little: her cheeks bright. Her hair was darkened by the wetness of the mist, but she appeared golden in the sudden moonlight. Before she was quite up, Tietjens almost kissed her. Almost. An all but irresistible impulse! He exclaimed: Steady, the Buffs!’ in his surprise. She said: Well, you might as well have given me a hand. I found,’ she went on, a stone that had I.R.D.C. on it, and there the lamp went out.’

Ford has great fun as these be-fogged lovers bumbling towards each other, comically hamstrung by English reticence. This golden moment in the dismal fog stays with Tietjens for years as he lurches from social embarrassment and dismissal to the horror of the trenches. It becomes his touchstone of a better reality, yet years later he cannot imagine her or his relation to her without referring to her formally:

He swore by the living God . . . He had never realised that he had a passion for the girl till that morning; that he had a passion deep and boundless like the sea, shaking like a tremor of the whole world, an unquenchable thirst, a thing the thought of which made your bowels turn over . . . But he had not been the sort of fellow who goes into his emotions . . . Why, damn it, even at that moment when he thought of the girl, there, in that beastly camp, in that Rembrandt beshadowed hut, when he thought of the girl he named her to himself Miss Wannop . . .

The odd pacing of this passage, its quick starts and turns, hopping from one ledge of awareness and self-parody to a surprised feeling captures this bedazzled shock of feeling and reflection. Valentine, too, struggles to imagine life in other than literary terms. Perhaps there is as yet no proper language for the new relationship between the sexes, a friendship, a keen but unspoken delight in sharing perceptions and understandings of things as yet opaque to themselves, let alone to one another. Valentine is comically confused, imagining:

She was going to leave that old school and eat pomegranates in the shadow of the rock where Penelope, the wife of Ulysses, did her washing.

When Tietjens returns from the war, she does not know what to expect, after years fantasizing being possessed by him sexually, she finds him strange and aloof. He withholds any show of affection despite years ago having proposed a night of sexual abandon. Earlier he had suffered shell shock. On his latest return, she hears he has sold all his belongings and cannot recall the names of close associates. Like other returning warriors, he may be violent. And yet, from the foggy morning mystery, eight years earlier, there is something between them:

She had, she said, known too many irregular unions that had been worthy of emulation and too many regular ones that were miserable and a cause of demoralisation by their examples . . . She was a gallant soul. She could not in conscience go back on the teachings of her whole life. She wanted to. Desperately! Valentine could feel the almost physical strainings of her poor, tired brain. But she could not recant. She was not Cranmer! She was not even Joan of Arc. So she went on repeating: I can only beg and pray you to assure yourself that not to live with that man will cause you to die or be seriously mentally injured. If you think you can live without him or wait for him, if you think there is any hope of later union without serious mental injury I beg and pray . . . ’ She could not finish the sentence . . . It was fine to behave with dignity at the crucial moment of your life! It was fitting: it was proper. It justified your former philosophic life. And it was cunning. Cunning!

Ford conveys this interior wandering and its comic turns from simplicity to elaborate learning. Valentine cannot make her desires clear to herself. Those novels have not yet been written, and so the turns of language, among travelers into this new terrain, fumble their way forward comically:

In one heart-beat apiece whilst she had been speaking they had been made certain that their union had already lasted many years . . . It was warm; their hearts beat quietly. They had already lived side by side for many years. They were quiet in a cavern. The Pompeiian red bowed over them; the stairways whispered up and up. They would be alone together now. For ever! She knew that he desired to say I hold you in my arms. My lips are on your forehead. Your breasts are being hurt by my chest!’ He said: Who have you got in the dining-room? It used to be the dining-room!’

[Valentine Wannop, portrayed by Adelaide Clemens, Is introduced protesting for women’s rights on the fairway of a distinguished gentlemen’s club. She is young and athletic and wins Tietjens support and soon after his affection.]

Parade’s End is a comic novel, born out of a decline and fall of great nonsense and the dawning of things bright and clever, decent and true, and still finding form. Ford writes with loving wit about treasures to be preserved from the debris of England’s history. In the end, Tietjens and Valentine retreat to a small town where Christopher sells antique furniture and they share odd views lovingly. Ford writes discontinuously, as times and scenes reform themselves, recollected in memory. The personal drawing boards on which all this takes place are fractured and fragmented. Satire helps clear away the rubbish, and provides author and reader wicked fun. Parade’s End offers hundreds of sparkling passages and a bracing welcome to renewal. Unlike so much modernist art, in the end, Ford’s trilogy is bright and invigorating.

ART: Ford Madox Brown, Ford’s grandfather, painted “Work," completed in 1865. It portrays a wide spectrum of social energies, high and low. Some of it is satirical, some sly and criminal, some pastoral and lyrical, but most of it celebrating the hard-laboring energies of the high Victorian moment. This effort to take it all in, captured in a few moments, appears in his grandson’s ambitious trilogy.